- ibiknowledge

Post-COVID Development – is it time to rethink the development paradigm?

France’s President Emmanuel Macron believes “the coronavirus pandemic will transform capitalism” and says that “it’s time to think the unthinkable”[1]. While this statement may seem extreme, it communicates a sense of urgency and a new reality we find ourselves in. For those of us involved in the delivery of foreign aid, is it also time to rethink the paradigm of development assistance?

The current USAID development assistance model generally consists of commissioning a program management contractor, who develops a work plan against pre-set desired outcomes and engages US and international technical experts. These experts travel to the country, provide expert knowledge to either improve capacity of the target country’s counter-part agencies, state and local governments and other institutions or otherwise provide various technical assistance in support of the country’s journey to self-reliance and national security. The chosen program management contractor oftentimes engages subcontractors, who have specialized knowledge or employ experts in a certain discipline to complement the capacity of the prime contractor to manage delivery.

This model relies on brick and mortar operations in the contractor’s home office and overseas, frequent travel by experts, together with allowances and differentials for enduring overseas hardships. In some countries, this also means additional costs of security to safeguard the contractor’s staff.

The COVID pandemic has forced many contractors to rapidly adapt to a new digital reality in order to continue performance under their current programs. To their surprise, many are finding that the quality of their work hasn’t been adversely affected during this “pilot” phase. This sudden event offered one choice – adapt or face the loss of work, termination of the program or major scale down. And as is often the case, necessity became the mother of invention, turning on surprising, innovative and creative platforms for delivering development technical assistance. For instance, an industry colleague on the Iraq Governance Performance Accountability (IGPA) project is leading it remotely from the US. USAID decided to continue with the project's activities by moving them online.

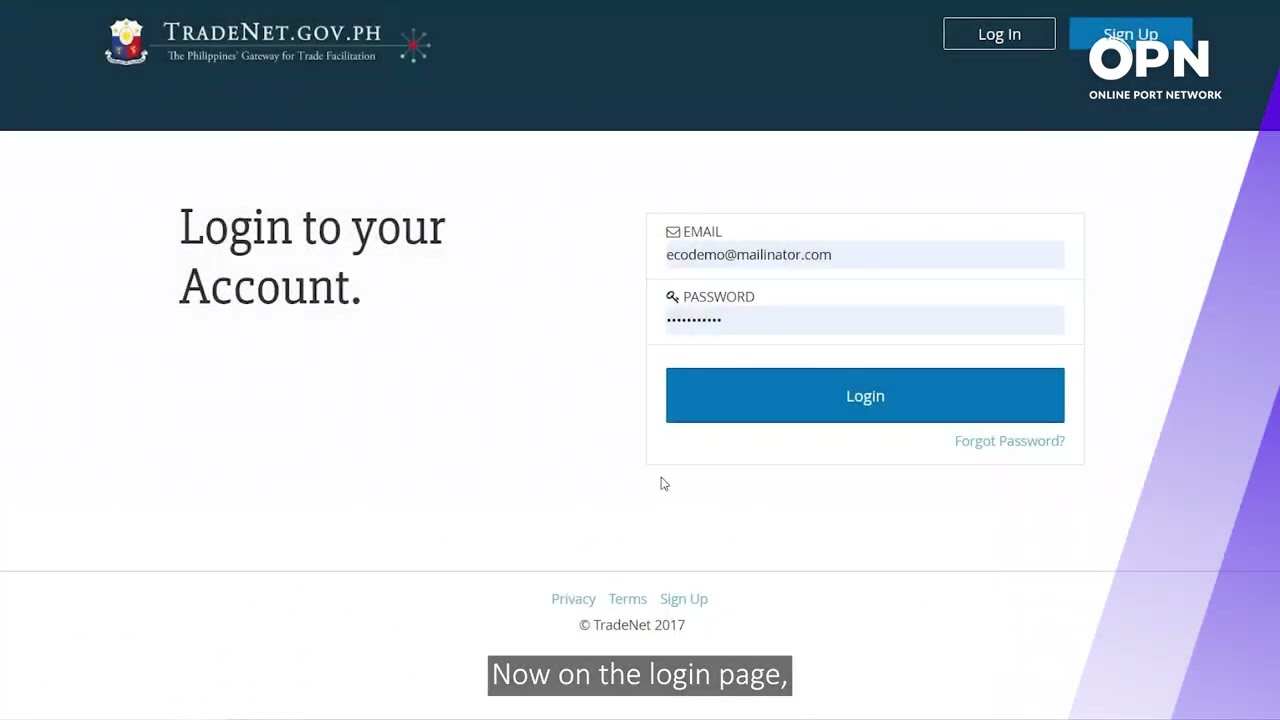

Where the technological infrastructure could support, programs continued capacity building activities, trainings and other interventions through virtual meetings/seminars via Google Hangouts, Zoom, and Microsoft Teams. Contractors repatriated their technical advisors who continue providing one-on-one assistance and collaborating with their overseas counter-parts through Office 365 capabilities. Mobile payments, remote procurements and GPS technologies are assisting with remote monitoring and validation.

If mandatory use of these new-found technological solutions could become the standard for future development program implementation, it could result in a major increase in efficiency and accountability by lowering the cost of delivery, removing redundancies, creating usable digital data and records ready for multi-purpose analysis, and, ultimately increasing the amount of assistance that reaches the intended counterparts.

We stand on the brink of a technological revolution that will fundamentally alter the way we live, work, and relate to one another. The First Industrial Revolution used water and steam power to mechanize production. The Second used electric power to create mass production. The Third used electronics and information technology to automate production. Now a Fourth Industrial Revolution is building on the Third, and is characterized by a fusion of technologies that is blurring the lines between the physical and digital spheres to optimize delivery of every possible service offering.[2] USAID recently launched its new Digital Strategy which seeks to promote secure, open, and inclusive country-level digital ecosystems and the programmatic use of digital technology in the Agency’s development and humanitarian assistance. The recently launched SpaceX Starlink global broadband program or its multiple competitors (Google Balloons etc.) will provide the much-needed high speed internet access around the globe, advancing the speed of this revolution.

The COVID-19 pandemic has forced donors and implementers to change, and we will continue to change based on this experience. The new competitive market realities will continue to compel companies to invest in technologies, digital platforms, new protocols, procedures and policies, in order to be able to perform their contracts and grants without interruptions or delays. This is a short-term fix.

Longer term, USAID’s implementing partners, who may have put these plans on the back burner, will need to accelerate thinking about broader business implications of the Fourth Revolution, which had started well before this pandemic. Additionally, they will have to seriously think about creating resilient systems within their own organizations to prepare for the next “black swan event” and beyond.

This new technology-based smart delivery model for USAID programs should inform all future program design whether through traditional agency procurement methods, co-creation, or new mechanisms that emerge as a result of technology use. As USAID rolls out and updates its new digital strategy, perhaps a consideration of this new delivery model should drive how the agency plans to adapt its own technology platforms and capabilities, in order to match the implementers’ changes.

[1] Financial Times, April 17, 2020

[2] Klaus Schwab, Founder and Executive Chairman, World Economic Forum